Economic prediction markets let you take positions on big-picture numbers and decisions like the next Fed rate move, monthly inflation, or this quarter’s GDP growth.

Instead of buying a stock, you trade a simple contract that settles at either $1.00 or $0.00, depending on what actually happens in the real world. If you’re new to prediction markets, think of each contract as a yes/no question with a price between $0.01 and $0.99.

Legal Economic Prediction Market Apps

Play $5 Get $75 In Fantasy EntriesUnderdog Predict Promo Code: BETUSA

Prediction Event Contracts is a derivatives product offered by Crypto.com | Derivatives North America (CDNA), an exchange regulated by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC). Trading CDNA Prediction Event Contracts involves risk and may not be appropriate for all. By trading you risk losing your cost to enter any transaction, including fees. You should carefully consider whether trading on CDNA is appropriate for you in light of your investment experience and financial resources. Any trading decisions you make are solely your responsibility and at your own risk.

Play $5 Get $75 In Fantasy EntriesUnderdog Predict Promo Code: BETUSA

Prediction Event Contracts is a derivatives product offered by Crypto.com | Derivatives North America (CDNA), an exchange regulated by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC). Trading CDNA Prediction Event Contracts involves risk and may not be appropriate for all. By trading you risk losing your cost to enter any transaction, including fees. You should carefully consider whether trading on CDNA is appropriate for you in light of your investment experience and financial resources. Any trading decisions you make are solely your responsibility and at your own risk.

Unlike online sportsbooks, legal prediction markets operate as exchanges regulated by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC). As a result, they serve customers in all fifty states.

Below, we explain how economic prediction markets work, where to trade legally, and the pitfalls unique to macro data so you can get started with confidence.

For the basics of prediction markets in general, see our beginners guide here:

Where to Bet on Economic Indicators in the USA

Several CFTC-regulated prediction markets offer a wide range of economics-related prediction markets, ranging from daily recurring markets to long-term policy outcomes.

Kalshi Economic Indicators

Kalshi is a US event-contract exchange regulated by the CFTC. Its economics catalog spans Fed policy decisions, CPI/PCE inflation, jobs data, GDP estimates, and more, each with clearly defined rules and sources.

Where Kalshi excels: Deep coverage of macro indicators; granular ranges (e.g., specific CPI or GDP ranges); clear rulebooks with named agencies and rounding; strong liquidity around scheduled release times.

What to know: Most markets settle on the first published number; rounding and range endpoints matter; liquidity clusters at 8:30 AM ET data drops and FOMC announcement windows, so plan entries/exits accordingly.

Read more: Kalshi Review

Polymarket Economic Prediction Markets

Polymarket lists fast-moving markets on economics and current events, offering continuous prices and a broad rotating menu.

Where Polymarket excels: Breadth and speed; new economics markets appear quickly around news cycles; active secondary markets help with pre- and post-release positioning.

What to know: Rule styles can vary by market, so always verify the data source, reference period, rounding, and tie-breakers; fees and liquidity differ by contract.

Read more: Polymarket Review

How Economic Prediction Markets Work

Most economic contracts are tied to scheduled releases or official announcements. The rules point to an exact source, such as the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) for CPI inflation, the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) for GDP, or the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) for interest rate decisions.

Because the source is fixed and the release time is known, economic prediction markets often build anticipation: prices can tighten as the clock ticks toward the announcement.

Two details matter a lot more than newcomers expect: precision and timing. Precision means the contract will specify exactly which number counts (for example, “Core CPI month-over-month, seasonally adjusted, rounded to one decimal place”).

Timing refers to the contract stating which version settles the market (for example, “first publication only,” also known as the “initial” or “advance” estimate). Knowing those two things helps you avoid surprises like revisions that affect settlement or decimals that flip outcomes.

Economic Prediction Market Example

Trading economic indicators is different from trading sports or politics. You aren’t just predicting a winner; you are often predicting a number.

Most economic markets are range-based and multi-outcome. Let’s look at a typical example: the Fed’s decision to change the federal funds rate range.

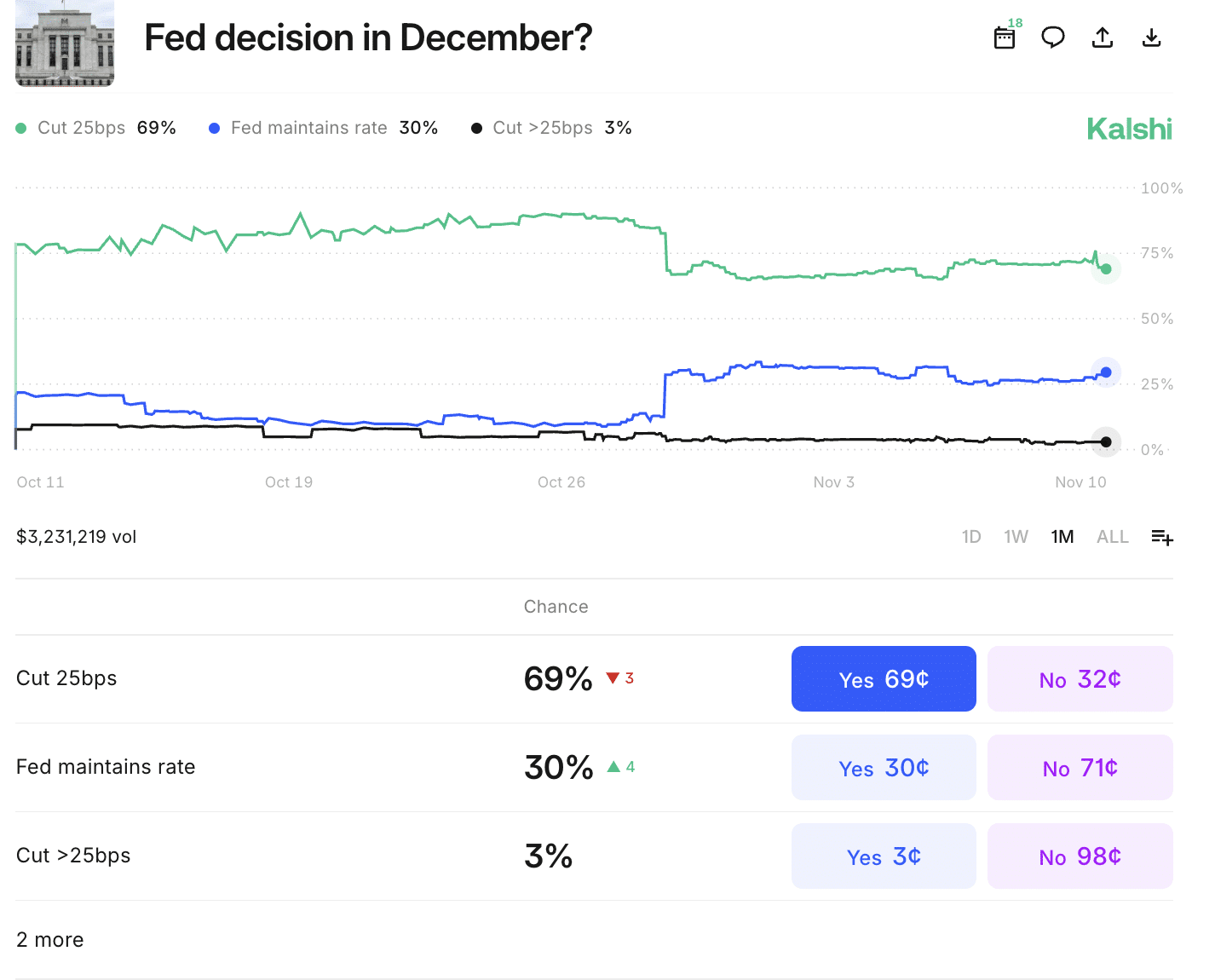

The market will ask: “Fed decision in December?”

The platform will then list several Yes/No contracts for different outcomes.

Here, the market believes a 25 bps cut is the most likely outcome, pricing it at 69¢ (or roughly 69%).

Example 1: The Speculator Trade (Trading the Data)

You’ve read several reports and believe the market is underestimating the chances that the Fed maintains the rate. You think the Federal Reserve is likely to maintain the current rate.

- Your Trade: You buy 100 “Yes” contracts on the “Fed maintains rate” range at 30¢ each.

- Your Cost: 100 contracts x 30¢ = $30.00

- The Result: The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) announces no change to the target federal funds rate.

- Your Payout: Your prediction was correct. Your 100 contracts, which you bought for $30, are now worth $1.00 each at settlement. You receive $100.00.

- Net Profit: $70.00 (minus fees).

Example 2: The Hedging Trade (Protecting Your Finances)

You own a small seasonal business that makes most of its income every summer. During the cooler offseason months, you park $500,000 in a high-yield business savings account to help cover your fixed monthly expenses.

A large rate cut would slash your interest income for the winter, forcing you to dip into the principal or take out a loan just to cover your fixed costs. A standard 25 bps cut is fine, but anything more is a problem.

- Your Trade: You decide to create a financial hedge. You buy 2,000 “Yes” contracts on the “Cut > 25 bps” range at 3¢ each.

- Your Cost: 2,000 contracts x 3¢ = $60

- The Result: Unexpectedly, the FOMC announces a 50 bps cut.

- Your Payout: Your hedge pays off. Your 2,000 contracts settle at $1.00 each, paying you $2,000.00.

Net Result: Your business savings account earns roughly $2,500 less interest during the offseason, but you gained $1,940 ($2,000 payout – $60 cost) from your trade. Your hedge successfully offset more than 75% of your financial loss.

Types of Economic Prediction Markets

Key Data Sources for Trading Economic Indicators

Unlike sports (stats) or politics (polls), economic markets are driven by official reports and analyst expectations. The “edge” often comes from correctly predicting how the official number will differ from the market’s consensus.

The Market-Moving Reports: Know the Calendar

Economic prediction markets are volatile around these key release dates:

| Report | What It Measures | When It’s Released |

| Consumer Price Index (CPI) | Inflation (cost of goods/services) | Monthly (second Thursday of the month, around the 13th) |

| Non-Farm Payrolls (NFP) | Job creation & unemployment rate | First Friday of the month |

| Gross Domestic Product (GDP) | The total value of all goods/services | Quarterly (Advance estimate) |

| FOMC Statement | Federal Reserve interest rate decisions | 8 times per year (see Fed calendar) |

The “Consensus” vs. The “Whisper Number”

- The Consensus: This is the official average forecast from major economists (e.g., from Reuters or Bloomberg polls). The market price will usually trade very close to this number.

- The “Whisper Number”: This is the unofficial expectation among expert traders, which may be higher or lower than the public consensus. The key to successful speculation is determining if the “whisper number” is more accurate than the public price.

The Official Sources (Resolution Sources)

Markets are not settled based on a news report; they are settled on the official data release from the relevant government agency.

- Inflation & Jobs: Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS)

- GDP: Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA)

- Interest Rates: The Federal Reserve (FOMC)

Tips for Trading Economic Prediction Markets

A successful strategy for trading economic indicators is less about “gut feel” and more about preparation. Because the “game” is the data release itself and the rules are ironclad, your entire plan should revolve around understanding the contract’s terms before you trade and knowing exactly when the key data drops.

Know the Rules

“Know the rules” sounds obvious, but there are some critical nuances in contract rules that can trip anyone up.

Additionally, it’s easy to underestimate the potential for rules to catch you off-guard because economic prediction markets should be simple in theory since they involve hard numbers from specific sources.

Here’s how to trade efficiently and avoid any unpleasant surprises:

Start with the source: The rules should name the agency or publication that determines the outcome. If it’s CPI, look for BLS. If it’s GDP, look for BEA. If it’s interest rates, look for the FOMC statement.

Next, pin down the measure. For example:

- “Headline” CPI includes everything, but “core” CPI excludes food and energy.

- “MoM” means month over month, and “YoY” means year over year.

- GDP often comes in “advance,” “second,” and “third” estimates for the same quarter, and many contracts settle on one specific estimate.

Then, find the reference period. The rules will say which month, quarter, or specific FOMC meeting applies. That keeps everyone on the same page about which data release determines the prediction market’s outcome.

Look for rounding and thresholds. Some contracts settle using one decimal place; others use two. A tiny difference (e.g., 0.3% versus 0.4%) can decide whether a contract pays $1.00 or $0.00. If the market uses ranges (e.g., “0.2% to 0.3%”), the rules will explain whether the endpoints are included.

Finally, check revisions and delays. Many economic numbers are revised later. Most contracts settle on the first publication and ignore subsequent changes, but don’t assume as such. Always read the line that says which version counts. If an agency delays a report, the rules will usually explain whether the market extends or pivots to a backup plan.

Plan Around Release Times

Economic data tends to drop at predictable times. Many reports arrive at 8:30 AM ET, while the Fed’s policy statement typically hits in the afternoon with a press conference soon after.

In practice, that means prices can move in three phases:

- Before the release (as forecasts change)

- At the moment the number lands (as everyone reads the print)

- Afterward (as traders digest details like revisions, seasonal adjustments, or the press conference tone).

A practical approach is to decide before the release how you’ll handle each scenario.

If the price already reflects your view, you may consider closing your trade early and taking the win. If your edge depends on reading the report quickly, plan how you’ll react to the number that matters for settlement (for example, “core MoM rounded to one decimal place”). Having a plan helps you avoid emotional decisions in a fast market.

Practice Responsible Trading

Plan your trade before the number hits the wire. Keep position sizes small relative to your account, avoid piling into a single threshold, and consider taking profits if the market moves your way ahead of the release.

Economic prints can be fast and unforgiving; a calm plan usually beats a hasty reaction.

Remember: the risk of loss is just as real when trading economic event contracts as when gambling at a casino game. Just because you’re dealing with hard economic data and trading alongside sophisticated financial professionals, it doesn’t mean “gambling addiction” isn’t a risk.

Key Risks & Pitfalls in Economic Markets

Trading economic data comes with unique risks that don’t exist in sports or politics. The biggest pitfalls aren’t just making a bad forecast, but rather misunderstanding how data is officially reported and what the market’s terms are actually asking.

Risk 1: The Data Revision

- The Problem: Unlike a sports game that ends, economic data is often revised by the government weeks or months after the initial release.

- The Rule: Prediction markets know this. The contract rules will always state which release they use for settlement. 99% of the time, this is the initial, advance, or first-published number.

- The Pitfall: Do not trade based on what you think the revised number will be. The market will settle on the first number, even if it’s later revised and proven “wrong.”

Risk 2: Misunderstanding the “Nitty-Gritty”

- The Problem: Economic terms are precise. “Inflation” and “Core Inflation” are different. “Recession” isn’t just two bad quarters of GDP; it’s a specific call by the NBER.

- The Pitfall: Always read the contract’s resolution rules. If you buy “Yes” on a recession and the market is using the NBER’s official declaration, your contract will expire worthless until that specific committee makes a call, even if the economy feels like it’s in a recession.